When studying history, people can often overlook its smaller aspects. Local history is often seen in a niche light – an aspect of communities on the same level as Parish Councils and Nimbyism, two parts of society stigmatised as bureaucratic and irritating. Yet the significance of local history should not be swept aside, and I will attempt to show that significance through one location of our own local history here in Harrogate: The Crimple Valley Viaduct.

Crimple Valley – an area between Harrogate and Pannal – is a composition of farmland (with several sheep) and small patches of woodland, intersected by several bridleways. Luxury houses surround the edges of the valley, and a small (dirty) river runs through its centre (although freshwater crayfish can be seen there recently). These are all trivial to the valley’s most well-known feature, the Crimple Valley Viaduct. The viaduct, completed in 1848, connects Leeds and York via rail, and is 571 meters in length. Most people’s knowledge of the area ends there – confined to train journeys, bike rides or the local Sunday walks of those who have too much free time on their hands and barely any social life.

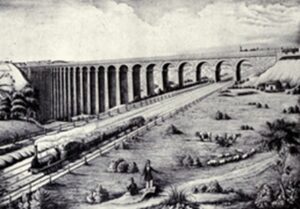

On my several Sunday walks down to the viaduct I have often marvelled at the area – of its untouched beauty and scale. On these walks I have met several elderly characters of Harrogate, all fascinated with the history of Crimple Valley. From many talks with them I have learned of the history of the area. The history of the viaduct is much older than 1848. The oldest point of interest that I have become known too is an old flour mill, located at 53°58’12.8″N 1°31’08.4″W. There is little evidence of the mill itself, in person or online, and now a private residence stands where it once potentially was. The only real visible evidence of it comes from a small millrun opposite – with two boulders indicating its presence, acting as a dam of sorts. Nevertheless, this mill (if it existed) was meant to be old – 1500s old. The next real key event for the valley, is with the introduction of a trainline, although not in the way you may think. The Leeds and Thirsk Railway (otherwise known as the Leeds Northern Railway) was a rail route connecting Leeds and Hartlepool. It was constructed in 1845, predating the viaduct. The line somewhat zig-zagged around the current location of the viaduct, and ultimately ran perpendicular to it. When the viaduct was finally built, the Leeds and Thirsk Railway continued to run, going under the viaduct. One artist interpretation from 1847 shows how two trains could run above and under the viaduct simultaneously.

The line would last until the 1960s when Dr Richard Beeching – infamous with local history buffs and train enthusiasts – closed several railway lines with his Beeching Axe (to cut costs) and the Thirsk Line was one that was famously axed – with many elderly locals in Harrogate still reminiscing on the old Thirsk line and station. Remnants of the line are still seen on the bridle paths – with the old track being covered over by wildflowers.

Nowadays, the valley has been contested, almost drowned in Nimbyism. Development proposals are a taboo, and Crimple Valley is rife with them. On the side of local history, crude developments can ruin the natural landscape of the area and really undermine the local history of the valley. The developers also sneakily get past prior rejections with constant bombardments of new proposals – which constantly be addressed. On the side of the developers, houses need to be built somewhere, and the approach of the Nimbys can be quite shrewd – several A4 sheets were placed around the valley with a recent development, titled with the caption ‘Those developers are at it again!’ (I always imagine a nasally manner of speech when reading that). But it is a complicated matter that needs to be addressed with great care really – primarily in the interests of residents.

Going back to the characters I meet whilst at Crimple Valley, the importance of the area to them is clear. One man I met was a 94-year-old gentleman, confined to his mobility scooter, called John. John was a proper Yorkshire soul. With a thick accent of ‘ee by gum,’ he would talk about how he would come down to the area at the break of day – all by his lonesome, wind or rain – just to enjoy the scenery. He had discussed the profound effect it had on his mental health, and how it had helped him with the past few years. In proper Yorkshire spirit, he asked that if he ever were to be found tipped over in the valley, that you should just put a coat over him, so he doesn’t get cold. It is easy to be sympathetic to ideals of local history, and its importance shouldn’t be understated.

International history is important, but one shouldn’t focus on it alone – instead they should be open to a variety of history. Last academic year, Head of History, Mr Russell, made a brief comparison about the Year 12 and Year 13 courses of the Russian Revolution to my class. He stated that the course went from the flawed yet slightly whimsical actions of the Tsars, to statistic after statistic about the number of deaths under Bolshevik rule (pretty depressing stuff really). I like to use the comparison of national and local news. Yes, national news of Rishi Sunak’s new environmental policies are much more important than a Look North report of local volunteers saving a fencing club for the elderly or a rowing society for dogs. Yet it can be a lot more wholesome to listen to the latter reports than more signs of governmental collapse (‘first they came for the Brummies, and I did not speak out – for I was not a Brummie’). To all those interested in history on any level, I give you this advice; it is sometimes ok to forgo your Orlando Figes, to boot your Mary Beard and shove your Simon Schama. To quote Ian McKellan’s Gandalf, ‘The world is not in your books and maps. It’s out there.’ Try to give time to research your local history and speak to characters like John about it – you never know what you might learn.